Diana, Princess of Wales, mother of Prince William and Prince Harry died in Paris car accident fifteen years ago today, on August 21, 1997. Over the next few weeks, I will look at Diana’s place in the history of the monarchy and her enduring influence over the current monarchy.

Queen of Fashion For most of English history, royal women set the fashions for ladies of the nobility. A visit to the National Portrait Gallery in London reveals rows of paintings of noblewomen dressed and coiffed to resemble their queen. During King Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, modest gable hoods that completely covered the hair were in vogue. Catherine introduced Spanish black work embroidery to the English court, a style that Henry VIII preferred for his shirts to end of his life.

Fashions changed when Anne Boleyn became a possible queen in waiting. Anne introduced numerous fashion innovations to the English court including more revealing French hoods that showed the hair and long sleeves that covered the hands. A court lady’s choice of hood might be a political statement in the late 1520s and 1530s as Henry VIII sought to annul his marriage to Catherine and marry Anne. The King’s third wife, Jane Seymour notably returned to the modest gable hood favoured by Catherine. One of the reasons for Anne of Cleves’s failure to successful perform the role of queen consort was the English court perception that her high waisted German style dresses were unflattering and she could not act as a leader of fashionable society.

Mary I and Queen Elizabeth I were expected to rule England in the manner of their male predecessors and set the fashion at court as their mothers had done. When Elizabeth I adopted farthingale skirts, wide neck ruffs and bejewelled wigs in the late sixteenth century, her ladies did the same. The distribution of printed images of the queen during the same period meant that women outside the court also knew how their monarch dressed and wanted to look just as fashionable. Elizabeth I insisted on the enforcement of sumptuary laws, fearing the breakdown of the social order and her subjects incurring large debts if women of all social backgrounds aspired to dress like the queen.

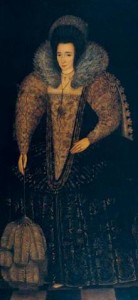

Stuart queens continued to play the role of fashion trendsetters during the seventeenth century. The ladies portrayed in the court portraiture of of Anthony Van Dyck in the 1620s and 1630s all resemble Charles I’s consort, Queen Henrietta Maria with tight curled hair, wide lace collars and full sleeves. When Charles II married Catherine of Braganza in 1661, one of his first gifts to his bride was a dress in the flowing, sensual style favoured by his mistress, Barbara, Duchess of Cleveland to replace the farthingale skirts still fashionable in new queen’s native Portugal.

Portrait of the Countess of Carlyle by Van Dyck. Her hairstyle and dress closely resemble that of Queen Henrietta Maria.

Royal wives and mistresses began to lose their exclusive influence over elite fashion trends after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. To shape fashion, it was necessary to be seen by the public, and the late Stuart and early Hanoverian royal families lived in increasing seclusion. William III and Mary II lived a quiet life at Kensington Palace because of the King’s asthma and discomfort in English society. Queen Anne’s health was shattered by her seventeen pregnancies. The first two King Georges could not speak English and the third was nicknamed “Famer George” for his love of country living at Kew Palace.

By the reign of George III, no lady of fashion claimed to be inspired by Queen Charlotte, the King’s homely and perpetually pregnant consort. The seclusion of the royal court and emergence of rival noble factions dictated by party politics brought new trendsetters to prominence. One of Diana’s Spencer predecessors, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire led fashionable English society in the late 1700s, inspiring the dresses worn by wealthy women.

The Duchess was a friend of Queen Marie Antoinette of France and helped popularize the white muslin dresses and floral embellishments favoured by the French queen during her “Petit Trianon” phase in the 1780s. As sumptuary laws had been repealed by the eighteenth century, anyone with the necessary funds attempted to imitate the Duchess’s style.

The Regency and Victorian periods occasionally revived the role of leader of fashion that had been the privilege of Tudor and Stuart royal women. Queen Victoria had a lasting impact on bridal fashions when she chose a simple white wedding dress and floral bouquet for her marriage to Prince Albert of Saxe-Cobourg. When Victoria retreated into mourning after Albert’s death in 1861, her daughter Princess Louise and daughter-in-law, Princess Alexandra became known as the most stylish members of the royal family, setting trends in late nineteenth century ladies fashion.

Queen Mary, consort of George V with Queen Elisabeth of Belgium in the 1920s. While the Queen of Belgium sports bobbed hair, a sleeveless dress and a boyish silhouette in the fashion of the time, Queen Mary still wears her long hair coiled in the Victorian style with a floor length, hourglass shaped dress.

By the twentieth century, however, royal women’s fashion had become synonymous with tradition instead of trend setting. Until the marriage of Prince Charles to Lady Diana Spencer, the clothes worn by royal women often seemed to hearken back to styles no longer worn by many of their subjects. Since George V disapproved of post World War One changes to ladies’ fashion, Queen Mary continued to wear floor length dresses in the hourglass style, as she had done during Queen Victoria’s reign.The conservative fashions favoured by the future George VI’s wife, Elizabeth were the antithesis of the trendy 1930s backless dresses worn by Wallis Simpson. In the 1960s, the Scotch tartans worn by Queen Elizabeth II and her children at Balmoral seemed very traditional within a fashion climate dominated by miniskirts and bell bottoms.

When Diana Spencer became Princess of Wales, in 1981, a royal woman once again set fashion as had been the case during the Tudor and early Stuart periods. In contrast to Elizabeth I or Henrietta Maria, Diana’s fashion choices were shown worldwide through photography and film.

At the annual State Opening of Parliament in the United Kingdom, the press eagerly photographed the princess and commented on her attire. Diana popularized the “princess style” wedding gowns of the 1980s with full skirts and sleeves. Her diverse fashions on official occasions ranged from the wide shouldered “Dynasty Di” ensembles of the 1980s, to elegant off shoulder evening gowns, to the form fitting sheath dresses of the 1990s. Diana’s admirers also imitated her casual wear, which included jeans with blazers and sleeveless tops with khakis.

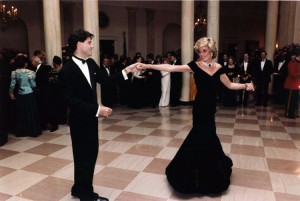

Diana, Princess of Wales, dancing with John Travolta at the White House on a state visit to the United States in 1985.

The emergence of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge as a twenty-first century fashion trendsetter reveals that Diana’s style had a lasting influence on the perceived role of royal women. As in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the public once again looks to princesses to influence the world of fashion.

The eager anticipation of Catherine’s choice of wedding dress in 2011 and and the sale of inexpensive versions of her outfits for women who wish to emulate her style reflects Diana’s enduring influence over popular expectations of royal women. Since Diana Spencer joined the royal family in 1981, royal women have once again assumed the Tudor-Stuart role of leader of fashionable society.

Next Week: Diana and the Royal Walkabout