When Duke Dimitri of Leuchtenberg, whose ancestors included Empress Josephine of France and Emperor Nicholas I of Russia, died in Saint Sauveur des Montagnes, Quebec, Canada in 1972, the Montreal Gazette published a long obituary with his picture. The headline was “Duke Dimitri Leuchtenberg dies, pioneered skiing in the Laurentians.” Dimitri’s journey from the court of his distant cousin, Emperor Nicholas II of Russia in St. Petersburg to the Pension Leuchtenberg ski chalet that he operated in St. Saveur was eventful and changed the history of alpine skiing in Canada.

Dimitri was born in St. Petersburg on April 30 (new style), 1898, the second of six children. His father, Duke George of Leuchtenberg was a great-grandson of Nicholas I through the marriage of the Emperor’s daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaievna to Maximilian de Beauharnais, third Duke of Leuchtenberg, a grandson of Napoleon I’s consort, the Empress Josephine. Maria and Maximilian had remained in Russia after their marriage and their children and grandchildren were treated as members of the extended Russian Imperial family.

By Duke George’s lifetime, many of the Leuchtenberg descendants had intermarried with the Russian nobility and held the title of Serene Highness. Although Duke George was related to the last Emperor of Russia, he was not one of the monarch’s close friends and his wife, Duchess Olga (nee Princess Olga Repnina) only saw the Imperial family on official occasions that brought all the Romanov descendants together.

Duke Dimitri enjoyed an upbringing typical of the Russian aristocracy in the early twentieth century. He was educated at the elite Russian Imperial Cavalry School and served in the White Russian Army during the Russian Civil Wars that followed the outbreak of Revolution in 1917. Duke George, Duchess Olga and their surviving five children ultimately fled Russia and settled in Castle Seeon in Bavaria, a property inherited by Duke George and his brother in 1891. While in exile, Duke Dimitri married a fellow member of the dispossessed Russian nobility, Ekaterina (Catherine) Arapova, in 1921 and she joined his family at Castle Seeon.

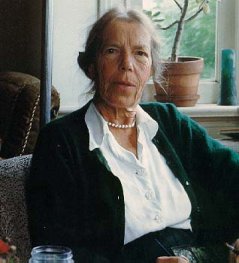

Photograph of Anna Anderson, the most famous of the numerous women who claimed to be Nicholas II's youngest daughter, Anastasia, after the murder of the Imperial family in 1922.

Although the Leuchtenbergs of Castle Seeon experienced continuous financial difficulties in the 1920s, Duke George was always willing to host fellow emigres in need on his Bavarian estate. In 1927, he welcomed “Anna Anderson,” the most famous of the numerous women who claimed to be Nicholas II’s youngest daughter, Grand Duchess Anastasia, following the murder of the Imperial family in 1918. Duke George confided to a friend, “I can’t tell you if she’s the daughter of the Tsar or not. But so long as I have the feeling that a person who belongs to my tight circle of society needs my help, I have a duty to give it (Peter Kurth, Anastasia: The Riddle of Anna Anderson, p. 177.)

Dimitri was deeply suspicious of his parents’ new house-guest. He knew Anastasia had belonged to a religious family yet Anderson seemed confused by the Russian Orthodox liturgy and crossed herself in the Roman Catholic manner. Dimitri and Catherine also witnessed a curious conversation between Anderson and Felix Schanzkowski, who initially recognized her as his sister Franzinska then retracted his statement after a brief conversation with the claimant. (For further information about Anna Anderson’s time with the Leuchtenbergs at Castle Seeon, see Greg King and Penny Wilson, The Resurrection of the Romanovs: Anastasia, Anna Anderson, and the World’s Greatest Royal Mystery, p. 152-161).

As financial pressures and tensions surrounding the identity of Anna Anderson increased in Castle Seeon, Dimitri and Catherine decided to start a new life for themselves in Canada. There had been a wave of White Russian immigration to Canada after 1917, which included some of the most prominent aristocratic families, such as the Ignatieffs. Dimitri was also a winter sports enthusiast and one of his relatives, the Marquis d’Albizzi had opened a guesthouse in the Laurentian mountains in 1924. In 1931, Dimitri and Catherine immigrated to Quebec.

At this time of the ducal couple’s arrival, the Laurentians were a comparatively remote farm region. The first rope tow ski lift had only been invented in 1930 and downhill skiing was a comparatively elite activity. Dimitri opened the first ski school in the region, teaching the guests at the Marquis d’Albizzi’s resort. Throughout the 1930s, Dimitri expanded his teaching activities, raising the profile of the Penguin ski club for female students at Montreal’s McGill University by helping train their competitors for downhill ski competitions. Dimitri also worked extensively as a surveyor, mapping new cross country trails in the Laurentian mountains. His work was widely admired by ski enthusiasts throughout North America and he was employed as a surveyor in the Rocky Mountains and New England.

At the same time, Dimitri and Catherine were frequently mentioned on the society pages of Montreal newspapers. The Montreal Gazette reported on November 6, 1937, “The Duke and Duchess Dimitri von Leuchtenberg, who arrived from the Empress of Britain from Europe where the spent the summer, are en route to their skiing camp at St. Saveur, where they will spend the winter.” In 1939, the Marquis d’Albizzi returned to Europe and Dimitri acquired his resort, renaming it the Pension Leuchtenberg. Following the Second World War, the Leuchtenbergs hosted distinguished guests at their resort including Governor General Vincent Massey and Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson.

Despite Dimitri’s new life in Canada, he never entirely escaped his family’s involvement in the Anna Anderson affair. On March 20, 1959, as Anderson’s case to establish her identity slowly unfolded in the West German courts, the Montreal Gazette reported, “Can Canadians Solve the Mystery of Anna Anderson-Anastasia?: German Lawyers Here.” The article reported, “Two whom they will meet this morning are Duke Dimitri of Leuchtenberg and his wife, now innkeepers in St. Saveur . . .he is convinced she is not Anastasia.” The lawyers also visited Nicholas II’s sister, Grand Duchess Olga, who was residing in Cooksville (now part of Mississauga), west of Toronto, at the time. Olga shared Dimitri’s conviction that Anna Anderson was not Anastasia.

Duke Dimitri died in St. Saveur at the age of seventy-four. He was survived by his wife, two daughters, three grandchildren and his brother Duke Constantine, who had immigrated to Ottawa. The remains of Grand Duchess Anastasia were unearthed after the collapse of the Soviet Union outside Yekaterinburg, where she was murdered with her family in 1918. DNA tests on tissue samples from Anna Anderson indicate that Dimitri’s suspicions were correct. She was Franzinska Schanzkowska and not a daughter of his distant cousin, the last Tsar of Russia.