1882 painting of King Muhammad XII of Granada surrendering to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile after the Fall of Granada in 1492

On January 2, 1492, King Mohammed XII of Granada, known to the Spanish as Boabdil, surrendered his capital to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile. The Moorish King’s capitulation ended the eight month siege of Granada and the the ten year war waged by Ferdinand and Isabella to unify all Spain under their leadership. The Fall of Granada, however, was not simply a change in political circumstances for the Iberian peninsula. For Ferdinand and Isabella, the reconquest of Granada was a religious crusade intended to replace the co-existence of Christian, Jewish and Muslim communities with a unified, Roman Catholic state.

From the establishment of the Caliphate of Cordoba in the 8th century, establishing Muslim rule over much of modern day Spain and Portugal through the gradual Christian reconquest of the Iberian peninsula during the later Middle Ages, Christian, Jewish and Muslim communities co-existed and lived in relative harmony. There was cultural exchange between members of the three religions, most notably in centres of learning such as the University of Salamanca.

Despite increased conflict between the three religions during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there was still evidence of interfaith co-operation and celebration in the decades immediately preceding the fall of Granada. When the future Queen Isabella’s sister-in-law, Blanca of Navarre arrived in Castile to marry King Enrique IV in 1441, the Chronicle of King Juan II recorded that in the village of Brivesca, “Following [the artisans] came the Jews with the Torah and the Moors with the Quran [dancing] in the manner usually reserved for [the entry of] kings who come to rule a foreign country. There were also many trumpets, tambourines, drums and flute players.” The celebrations accompanying Blanca’s arrival demonstrated the enduring tradition of interfaith co-operation and coexistence in medieval Spain.

Isabella, Ferdinand and Muhammad had few examples of harmony or coexistence in their own early lives. All three future rulers were born into uncertain circumstances and had to fight for their place in the royal succession. Isabella was born in 1451, the daughter of King Juan II of Castile and his second wife, Isabel of Portugal. Her father died when she was three and her mother increasingly withdrew from public life due to depression. Isabella’s elder half-brother, Enrique IV did not allow Isabel full access to her dower income and the family lived modestly for royalty. According to the chronicler Fernando del Pulgar, “The Queen, Our Lady, from childhood was without a father, and we can even say a mother . . . She had work and cares, and an extreme lack of necessary things.”

In Aragon, Isabella’s second cousin Ferdinand, born in 1452 as the son of King Juan II of Aragon and his second wife, Juana Enriquez, faced the potential collapse of his kingdom before ascending to the throne. The region of Catalonia was determined to regain its independence and the elderly King Juan did not appear to have the energy or authority to maintain the cohesion of his kingdom. The young Ferdinand and his mother assumed authority over the conflict with Catalonia.

At sixteen, Ferdinand was already a politically active figure, addressing the Parliament of Aragon in Zaragoza in 1468, “Lords: You all know with what hardships my lady mother has sustained the war to keep Catalonia within the House of Aragon. I see my lord father old and myself very young. Therefore I commend myself to you and place myself in your hands and ask you to please consider me as a son.”

In Castile, Isabella was determined to avoid marriage to a distant sovereign that would prevent her from eventually succeeding her brother, Enrique. The King of Castile was unpopular and his acknowledged daughter Juana was rumoured to be illegitimate, circumstances that improved Isabella’s political situation. In 1469, the eighteen year old Isabella entered into secret negotiations with seventeen year old Ferdinand and the Prince slipped into Castile disguised as a servant so they could be married without the knowledge of Enrique IV.

Isabella became Queen of Castile in 1475 and spent the early years of her reign fighting factions loyal to Infanta Juana. Ferdinand became King of Aragon in 1479. The “Catholic Kings” as the royal couple were known acted as partners throughout their kingdoms. A German visitor to the court of Castile in 1484, Nicolaus von Poppelau observed, “The King did nothing without the consent of the queen; he did not seal his own letters until the queen had read them, and if the queen did not approve of one of them the secretary tore it up in the presence of the King himself.” Isabella’s authority within her marriage was unusual as lands belonging to royal heiresses of this period were often controlled by their husbands.

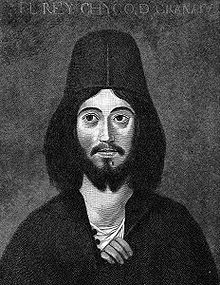

Ferdinand and Isabella shared the goal of reconquering Granada throughout their reigns. The fall of the last Moorish kingdom in the Iberian peninsula would not only contribute their religious goals but neutralize a political threat in the person of Muhammad XII. Muhammad became King of Granada in 1482 following the expulsion of his unpopular father, King Abu l-Hasan Ali. To prove his ability to rule over the competing claims of his uncles and exiled father, Muhammad invaded Castile on numerous occasions. The conquest of Granada allowed Isabella and Ferdinand to impose Roman Catholicism on all of modern day Spain and neutralize any threats to their authority and religion. Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism were expelled from the Iberian peninsula in 1492 and the Isabella and Ferdinand created the Spanish Inquisition to investigate the sincerity of conversions.

The explorer Christopher Columbus was present at Mohammad XII’s surrender and described the event in a letter to the Catholic Kings, “After your Highnesses ended the war of the Moors who reigned in Europe, and finished the war of the great city of Granada, where this present year on the 2nd January I saw the royal banners of Your Highnesses planted by force of arms on the towers of the Alhambra, which is the fortress of the said city, I saw the Moorish sultan issue from the gates of the said city, and kiss the royal hands of Your Highnesses.” The fall of Granada provided Queen Isabella with the funds to provide Columbus with ships for his first Atlantic voyage in 1492.

Ferdinand and Isabella’s goal of a unified Spain, however, proved elusive. The death of their only son, Juan, resulted in the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon becoming part of the Holy Roman Empire during the reign of their daughter Juana’s son, Emperor Charles V. The dynastic union of Aragon and Castile would not become a formal political union until the reign of the first Bourbon King Philip V, following the War of the Spanish Succession in the early eighteenth century. The Battle for Spain increased the wealth and religious authority of the Catholic Kings but the political unification of Castile and Aragon would not occur for another two centuries.

Further Reading:

Next Weekend: Napoleon, Josephine and the French Caribbean