Detail from "The Trial of Queen Caroline, 1820" by George Hayter, showing the Queen with her lawyers before the House of Lords

As the worldwide press discusses the photographs from Prince Harry’s recent holiday in Las Vegas, it is worth remembering the royal scandal that created modern tabloid coverage of royalty. The 1820 trial of Queen Caroline also involved evidence of semi-public nudity in a hotel suite by a member of the royal family traveling abroad, and was the subject of discussion in both parliament and broader society. The accusation leveled against the King and Queen during the proceedings undermined the reputation of the monarchy.

In 1820, the new King George IV was determined to obtain a divorce from his estranged wife, Caroline of Brunswick. As the only legal grounds for divorce at the time were adultery, the King brought the Pains and Penalties Bill before parliament, requesting that the marriage might be dissolved and Caroline deprived of the title of queen because of her alleged infidelity with Italian courtier, Bartolomeo Pergami during her travels on the continent. Queen Caroline returned to London for the reading of the bill, which amounted to a public trial with the nation’s representatives as judges and jury.

The English public have always taken an interest in the breakdown of a royal marriage. Seditious speech cases from the reign of Henry VIII demonstrate that “The King’s Great Matter” captured the popular imagination with English women in particular sympathizing with the King’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon and disapproving of his second wife, Anne Boleyn.

When King George I ascended to the thrones of England and Scotland in 1714, scurrilous verses circulated lampooning his perceived mistresses as “the elephant” and “the maypole” and expressing sympathy for his estranged wife, Sophia Dorothea of Celle, who was imprisoned in Ahlden Castle for her alleged adultery. Although printed political pamphlets had existed in the British Isles since the English Civil Wars, high rates of illiteracy and the difficulty spreading news to a predominantly rural population impeded the cohesion of a informed public.

Caricature of King George IV and Queen Caroline in the form of the green bags of evidence brought before parliament to support the guilt or innocence of the Queen. King George has a beard and build reminiscent of King Henry VIII and Caroline is wearing the same feather headdress she wore to parliament.

In 1820, the public audience for the Trial of Queen Caroline was very different from the groups who commented on the marriages of Henry VIII or George I. The British Isles had become increasingly urbanized with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, allowing news to travel more quickly. Literacy rates had increased and those who were illiterate could listen to news being read aloud in the pub, coffeehouse or town square.

In 1816, publisher William Cobbet introduced a single sheet version of The Register, a political digest available for a tuppence. The Register brought the news of the trial of Queen Caroline to a wide public audience who already disapproved of George IV’s extravagance during the recession that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars. While the King assumed his subjects would disapprove of the Queen’s behaviour abroad, the public instead sympathized with Caroline, who appeared to be the target of base accusations that brought the monarchy into disrepute

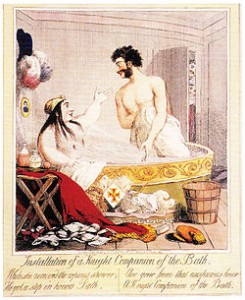

Political cartoon of Queen Caroline taking a bath with Pergami, based on the accusations leveled against the Queen.

The public eagerly followed the scandalous revelations in parliament through the newly published twopenny broadsheets. Witnesses supporting the King’s motion presented evidence that the Queen had been seen in the arms of her Italian lover in various states of undress during her travels and that they bathed together. One of the Queen Caroline’s Italian servants testisfied before the House of Lords that the Queen employed a male exotic dancer and demonstrated aspects of the dance before the assembled peers (Jane Robins, Rebel Queen, p. 213-214).

In response to these accusations, the Queen’s attorney, Lord Brougham threatened to reveal secrets about George IV’s personal life that would damage the monarchy. Brougham also argued that the witnesses for the prosecution had been bribed and that the Queen was the victim of a conspiracy to undermine her reputation so that the King might remarry and have more children. George’s and Caroline’s only child, Princess Charlotte, had died in childbirth three years previously and Brougham argued this event was the impetus for the Pains and Penalties Bill (Flora Fraser, The Unruly Queen: The Life of Queen Caroline, p. 434). The defence concluded by comparing George IV to the Roman Emperor Nero, who degraded his wife’s reputation so that he could put her aside and marry his mistress.

After the reputations of King George IV and Queen Caroline had been debated in parliament and amongst the readership of The Register, the Pains and Penalties Bill passed the House of Lords by a narrow margin. Public support for the Queen, and the near certainty that the House of Commons would defeat the bill, however, resulted in the government withdrawing the motion. Londoners celebrated in the streets, smashing the windows of government buildings and the offices of newspaper editors who had supported the King. Despite the failure of the divorce proceedings, George barred Caroline from his coronation, resulting in a public disturbance as the Queen stood outside the doors of Westminster Abbey, demanding entrance. The broadsheets naturally covered the continuing public conflict between the King and Queen.

The Trial of Queen Caroline was a turning point in the history of the monarchy. For the first time, the collapse of a royal marriage unfolded in twopenny broadsheets that were accessible to members of all social backgrounds. The King’s attempts to undermine the Queen’s reputation to secure a divorce made him deeply unpopular with his subjects. The reign of George IV’s niece, Queen Victoria would return the monarchy to respectability but public access to information about royal scandals through the press has persisted to the present day.

i want to know of the ethical obligations in this trial by lord brougham

Check out ‘George IV’ by Christopher Hilbert.

I am aroyl fan I have a couple of books