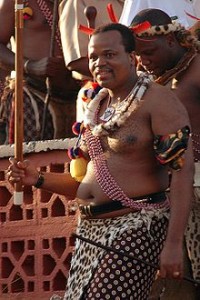

King Mswati III of Swaziland, participating in the 2006 Reed Dance, a ceremony where unmarried women pay tribute to his mother and co-ruler, Queen Ntombi.

The Economist has been devoting recent attention to the world’s few remaining absolute monarchies. While last week’s issue contained a detailed analysis of Sheikha Mayassa of Qatar’s art patronage, an article discussing presidential motorcades this week, You Got a Fast Car, describes King Mswati III of Swaziland’s lavish collection of automobiles. The Tracy Chapman song referenced in the article’s headline is about a young woman’s attempts to escape poverty but the lavish Swazi motorcade draws attention to the divide between the opulent lifestyle of the royal family and the challenges faced by their subjects.

The Economist correspondent explains, “The Swazi regal convoy can be up to 20 cars long. The king’s favourite vehicles include a $625,000 Rolls Royce, a $500,000 Maybach 62 and a BMW X6. He also has 20 Mercedes Benz S600 Pullman Guards, costing $250,000 each, many of them armoured. Warrior guards in traditional dress including an “Emajobo” or loin skin travel with the king. “These men emerge from cars already sprinting,” said one local observer.” Although he reigns in the 21st century, King Mswati faced the same mixed responses to this show of wealth that absolute monarchs have always encountered from the their subjects. The correspondent observes that some Swazis are disgusted by the King’s lavish spending while others express pride that Swaziland presents the finest state motorcade in Africa.

In the film, the Princess is seen engaging in charity work but the King rationalizes his absolute rule and lavish lifestyle. The numerous palaces, private jets and fancy cars enjoyed by the King are contrasted with the poverty experienced by many of his subjects. Swaziland has the highest rate of HIV infection in the world (at least 26% of adults) and one of the lowest life expectancies (48 years as of 2012). A 2005 general strike included participants holding signs that read “No to more palaces, cars and parties,” a reference to $20 millon the King spent building eight palaces in 2004.

The perception of insensitive extravagance has cost previous absolute monarchs their thrones. One of the most recent African examples is King Farouk I of Egypt who reigned from 1936 until he was deposed in 1952. Farouk was famous for his lavish lifestyle, encompassing dozens of palaces, hundred of cars and lavish shopping sprees in Europe. There were rumours that he ate 600 oysters a week. Criticism of this lifestyle increased when he showed insensitivity to the hardships experienced by his subjects during the Second World War. He kept his palace in Alexandria fully lit while the city’s other inhabitants experienced a blackout due to German and Italian bombing. This reputation for luxury combined with insensitivity directly precipitated his removal from the throne in 1952. Farouk continued his lavish lifestyle after he was deposed, dying at the table of a fancy French restaurant after a large gourmet meal in 1965.

The political future of Swaziland’s royal family remains uncertain. Four days of popular protests are planned for April 12 to mark the anniversary of the 1973 ban on political parties. The King appears unwilling allow his kingdom to evolve into a constitutional monarchy but, as the Economist states, reactions to his extravagance continue to be mixed, preventing a unified opposition to his absolute rule.